Mawlid al-Nabi

Across the globe, including in the United States, Mawlid al-Nabi is celebrated on October 7 and 8, or the twelfth day of the month Rabi al-Awwal. This day celebrates the birthday of the Prophet Muhammad! While some Muslims choose not to participate in this observance - feeling it places too much emphasis on the Prophet as human and distracts from the true divine source of revelation - other Muslims view this festival as a way to teach their communities about the Prophet Muhammad's way of life, which all Muslims seek to emulate. For those who do celebrate Mawlid al-Nabi, there is much to do. Many celebrate privately in their homes, others decorate their local mosque with lights and hold large festive gatherings, and still others celebrate by sharing food, attending lectures about the Prophet's life and virtues, Salawat prayer services, participating in marches, and reciting the Qur'an, litanies, and devotional poetry of the Prophet.

In some countries, like Pakistan, the entire month of Rabi’ al-Awwal is observed as the Prophet’s “birth month.” In Singapore, the observance of Mawlid al-Nabi is a one-day festival that often includes special “birthday parties” for poor children and orphans in addition to the regular prayers and lectures in local mosques. Azhar Square in Cairo is the site of one of the largest celebrations, with over two million Muslims in attendance.

The American Muslim community brings their distinct customs to the festival observance of Mawlid al-Nabi. Mosques and Muslim student organizations at universities across the U.S. hold events commemorating the Mawlid; this may include lectures, recitation of praise poetry, and Salawat prayer services in which God is invoked to send blessings on the Prophet, his family, and his followers. Some Islamic centers hold special programs for children, where they learn about the character and life of the Prophet, how he handled challenges, and how he responded to his enemies and his friends. Children often prepare essays or skits that present important teachings or events in Muhammad’s life. Many Muslims feel that the celebration of the Prophet’s birthday is particularly important in the American context and have therefore begun to add distinctly American elements as part of its celebration. The various ways in which American Muslims adopt the celebration of Mawlid al-Nabi show both their love for the Prophet and their dedication to passing these traditions on to the next generation.

Indigenous Peoples' Day (previously, Columbus Day)

Since 1991, numerous cities, universities, and states have adopted Indigenous Peoples’ Day – a holiday that celebrates the history and contributions of Native Americans. Not by coincidence, the occasion usually falls on Columbus Day, the second Monday in October, or replaces the holiday entirely. Why replace Columbus Day with Indigenous Peoples’ Day? Many have long argued that holidays, statues, and other memorials to Columbus sanitize his actions—which include the enslavement of Native Americans—while giving him credit for “discovering” a place where people already lived.

During the President’s proclamation on Indigenous Peoples’ Day last year, President Biden acknowledged that “Since time immemorial, American Indians, Alaska Natives, and Native Hawaiians have built vibrant and diverse cultures — safeguarding land, language, spirit, knowledge, and tradition across the generations…For generations, Federal policies systematically sought to assimilate and displace Native people and eradicate Native cultures. Today, we recognize Indigenous peoples’ resilience and strength as well as the immeasurable positive impact that they have made on every aspect of American society. We also recommit to supporting a new, brighter future of promise and equity for Tribal Nations — a future grounded in Tribal sovereignty and respect for the human rights of Indigenous people in the Americas and around the world.“ He continues, adding that “On Indigenous Peoples’ Day, we honor America’s first inhabitants and the Tribal Nations that continue to thrive today. I encourage everyone to celebrate and recognize the many Indigenous communities and cultures that make up our great country.”

Biden's proclamation last year marks the first time a U.S. president has officially recognized Indigenous Peoples’ Day and signifies a formal adoption of the holiday – something that a growing number of states and cities have already come to acknowledge. While Indigenous Peoples’ Day can’t fully address the erasure of Native American history from public education on its own, it does offer a time to focus on this history in schools and other settings where many history textbooks and discussions leave out Native Americans or sanitize white colonizer’s treatment of them.

There are no set rules on how one should appreciate the day, said Van Heuvelen, a member of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe from South Dakota. It's all about reflection, recognition, celebration and education. "It can be a day of reflection of our history in the United States, the role Native people have played in it, the impacts that history has had on native people and communities, and also a day to gain some understanding of the diversity of Indigenous peoples," she said. In Berkeley, for example, in 2017 the Indigenous Peoples’ Day Committee celebrated the holiday’s 25th anniversary in the city with dancing, food, and songs from local Native American tribes. Berkeley was the first city to adopt Indigenous Peoples’ Day back in 1991, and it continues to mark the holiday by highlighting both the history and contemporary culture of Native peoples.

Diwali

Every year in October or November, millions all across the world celebrate Diwali - a five-day festival that marks one of the biggest and most important holidays of the year in India. While the dates vary annually based on the Hindu lunar calendar, Diwali usually occurs in October or November. This year the festival will run from October 22 to October 26 with the biggest day of festivities, Lakshmi Puja, taking place on October 24. Although the exact date of Lakshmi Puja changes every year, it is always held on the night of the new moon preceding the Hindu month of Kartika. The religious celebration, which is also referred to as the Festival of Lights, is an auspicious occasion that celebrates the triumph of light over darkness, good over evil, and hope over despair. Originally a Hindu celebration, over the centuries Diwali has become a national festival that's enjoyed by non-Hindu communities as well. For instance, in Jainism, Diwali marks the nirvana, or spiritual awakening, of Lord Mahavira on October 15, 527 B.C.; in Sikhism, it honors the day that Guru Hargobind Ji, the Sixth Sikh Guru, was freed from imprisonment. Buddhists in India celebrate Diwali as well.

The festival of Diwali gets its name from the row (avali) of clay lamps (deepa) that Indians light outside their homes to symbolize the inner light that protects them from spiritual darkness. During this time, Sri Maha Lakshmi—the goddess of wealth, abundance, and well-being—is the main deity worshipped, so across India, many people light lamps and candles to entice Lakshmi to visit their homes.

Each day of Diwali has its own special significance. On the first day, Dhanteras, people will perform offering rituals called pujas or poojas, place tea lights around the balconies or entryways of their homes, and purchase kitchen utensils (which are believed to bring good fortune). Day two, Narak Chaturdashi, is a time many people will spend at home, exchanging sweets with friends or family and decorating the floors of their home with rangolis - intricate patterns made from colored powder, rice, and flowers. Day three is Lakshmi Puja, the main celebration and believed to be the most auspicious day to worship the goddess Lakshmi. Families dress up and gather for a prayer to honor her followed by a delicious feast, fireworks, and more festivities. The fourth day, Govardhan Puja is associated with Lord Krishna and the Gujarati new year and is a time generally spent preparing a mountain of food offerings for Puja. The fifth and final day - Bhaiya Dooj - is dedicated to celebrating the bond between siblings. Traditionally, brothers will visit and bring gifts to their sisters who in turn honor them with special rituals and sweets.

In 2009, former President Barack Obama became the first sitting U.S. President to observe Diwali, and in 2016, he marked the holiday by lighting a diya in the Oval Office. "As Hindus, Jains, Sikhs, and Buddhists light the diya, share in prayers, decorate their homes, and open their doors to host and feast with loved ones, we recognize that this holiday rejoices in the triumph of good over evil and knowledge over ignorance," he said in a Facebook post at the time. In 2020, just days after being elected the first Black, South Asian, and woman Vice President, Kamala Harris took to social media to mark the auspicious holiday as well. "Happy Diwali and Sal Mubarak!" she wrote. "@DouglasEmhoff and I wish everyone celebrating around the world a safe, healthy, and joyous new year."

Samhain

Each year Samhain is celebrated at the midpoint between the fall equinox and the winter solstice. Samhain is a pagan religious festival originating from an ancient Celtic spiritual tradition. In modern times, Samhain (a Gaelic word pronounced “SAH-win”) is usually celebrated from October 31 to November 1 to welcome in the harvest and usher in “the dark half of the year.” Many celebrants believe that the barriers between the physical world and the spirit world break down during Samhain, allowing more interaction between humans and denizens of the Otherworld.

Once upon a time, Ancient Celts marked Samhain as the most significant of the four quarterly fire festivals. During this time of year, hearth fires in family homes were left to burn out while the harvest was gathered. Celebrants then joined with Druid priests to light a community fire using a wheel that would cause friction and spark flames. The wheel was considered a representation of the sun and used along with prayers. Cattle were sacrificed to the Celtic deities and participants took a flame from the communal bonfire, believed to help protect them during the coming winter, back to their home to relight the hearth.

Because the Celts believed that the barrier between worlds was breachable during Samhain, they prepared offerings that were left outside villages and fields for fairies, or Sidhs. It was expected that ancestors might cross over during this time as well, and Celts would dress as animals and monsters so that fairies were not tempted to kidnap them. Some specific monsters were associated with Samhain, including a shape-shifting creature called a Pukah, the Lady Gwyn, the Dullahan, the Faery Host, and Sluagh. Many stories were told during these festivals as well, among them "The Second Battle of Mag Tuired" and "The Adventures of Nera."

By the 9th century, the influence of Christianity had spread into Celtic lands, where it gradually blended with and supplanted older Celtic rites. All Souls’ Day was celebrated similarly to Samhain, with big bonfires, parades and dressing up in costumes as saints, angels and devils. The All Saints’ Day celebration was also called All-hallows or All-hallowmas (from Middle English Alholowmesse meaning All Saints’ Day) and the night before it, the traditional night of Samhain in the Celtic religion, began to be called All-Hallows Eve and, eventually, Halloween. Around the 1980s, a broad revival of Samhain resembling its traditional pagan form began with the growing popularity of Wicca. Wicca celebrations of Samhain take on many forms, from the traditional fire ceremonies to celebrations that embrace many aspects of modern Halloween, as well as activities related to honoring nature or ancestors.

Halloween

The celebration of Halloween was extremely limited in colonial New England because of the rigid Protestant belief systems there. Halloween was much more common in Maryland and the southern colonies. As the beliefs and customs of different European ethnic groups and the American Indians meshed, a distinctly American version of Halloween began to emerge. The first celebrations included “play parties,” which were public events held to celebrate the harvest. Neighbors would share stories of the dead, tell each other’s fortunes, dance and sing. Colonial Halloween festivities also featured the telling of ghost stories and mischief-making of all kinds. By the middle of the 19th century, annual autumn festivities were common, but Halloween was not yet celebrated everywhere in the country.

In the second half of the 19th century, America was flooded with new immigrants. These new immigrants, especially the millions of Irish fleeing the Irish Potato Famine, helped to popularize the celebration of Halloween nationally. Borrowing from European traditions, Americans began to dress up in costumes and go house to house asking for food or money, a practice that eventually became today’s “trick-or-treat” tradition. Young people believed that on Halloween they could divine the name or appearance of their future spouse by doing tricks with yarn, apple parings, or mirrors.

Not long after this, there was a move in America to mold Halloween into a holiday more about community and neighborly get-togethers than about ghosts, pranks, and witchcraft. At the turn of the century, Halloween parties for both children and adults became the most common way to celebrate the day. Parties focused on games, foods of the season, and festive costumes. Parents were encouraged by newspapers and community leaders to take anything “frightening” or “grotesque” out of Halloween celebrations. Because of these efforts, Halloween lost most of its superstitious and religious overtones by the beginning of the twentieth century.

By the 1920s and 1930s, Halloween had become a secular but community-centered holiday, with parades and town-wide Halloween parties as the featured entertainment. Between 1920 and 1950, the centuries-old practice of trick-or-treating was also revived. We still do many of these things today along with costume parties, campfire stories, spooky movies, carving jack-o-lanterns, and other seasonal traditions.

- Learn More

-

Image

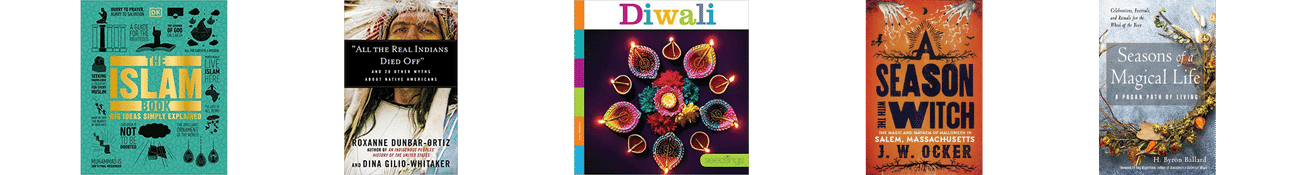

The Islam Book by Dorling Kindersley Limited

This essential guide to Islam covers every aspect of the Muslim faith and its history – from the life of the Prophet Muhammad and the teachings of the Koran to Islam in the 21st century in an easy to follow layout. Find out about modern issues such as fundamentalism, the work of peaceful traditionalists, modernizers, and women's rights campaigners, as well as the central tenets of Islam, such as prayer, fasting, and pilgrimage.

"All the Real Indians Died Off": and 20 other myths about Native Americans by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz

In this enlightening book, scholars and activists Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz and Dina Gilio-Whitaker tackle a wide range of myths about Native American culture and history that have misinformed generations. Tracing how these ideas evolved, and drawing from history, the authors disrupt long-held and enduring myths such as “Columbus discovered America", “Thanksgiving Proves the Indians Welcomed Pilgrims”, and “Sports Mascots Honor Native Americans.”

Part of our children's non-fiction collection, this title provides a basic introduction for all ages to the festival of Diwali. Check out our databases like World Book and Florida Electronic Library to learn more.

A Season With the Witch: the magic and mayhem of Halloween in Salem, Massachusetts by J. W. Ocker

For the fall of 2015, occult enthusiast and Edgar Award-winning writer J.W. Ocker moved his family of four to downtown Salem to experience firsthand a season with the witch, visiting all of its historical sites and macabre attractions. In between, he interviews its leaders and citizens, its entrepreneurs and visitors, its street performers and Wiccans, its psychics and critics, creating a picture of this unique place and the people who revel in, or merely weather, its witchiness.

Seasons of a Magical Life: a pagan path of living by H. Byron Ballard

This book looks at the agricultural year as a starting space for a deepening of earth-centered spirituality. It gives a set of backstories to ease the reader into a time between the pre-industrial era and the modern one, into a place where the fast-moving stress of American life can be affected by a better connection not only to the natural world but to the elegant expression of the year as expressed through seasonal festivals and celebrations.

Descriptions adapted from the publisher.