The History of Senbazuru

Folding 1,000 origami cranes, senbazuru, is a tradition that originated from an ancient Japanese legend. The legend claimed that anyone who folded 1,000 paper cranes would be granted either a lifetime of happiness and good luck or one wish. The practice became more widely popularized after the death of 12-year-old Sadako Sasaki in 1955.

Sadako Sasaki was two years old when the United States dropped an atomic bomb on the city of Hiroshima. Ten years later, Sadako developed leukemia as a result of the radiation exposure and was hospitalized for treatment. After learning about the legend of 1,000 cranes from her father, Sadako attempted to fold 1,000 cranes from her hospital room in hopes that it would grant her a wish. An exhibit about Sadako at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum states that she completed her goal before she passed away on October 25, 1955. A popular fictionalized account of her life, however, claims she was only able to finish 644, and the final 356 were folded by friends and loved ones.

Since her death, Sadako Sasaki has become a symbol for the long-reaching and devastating effects of nuclear war. Because of her story, the act of folding 1,000 origami cranes has become more closely associated with wishes for peace and health. In 1958, the Children's Peace Monument was created by artists Kazuo Kikuchi and Kiyoshi Ikebe in remembrance of the thousands of children who died due to the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. The top of the monument depicts Sadako Sasaki standing in front of an origami crane. The monument itself is surrounded by glass cases filled with thousands of folded cranes sent from countries all around the world.

Because of their modern association with peace and good health, senbazuru are often brought to war memorials or hospitals. When left at memorials, they act as prayers for peace and the end of conflict. At hospitals, they are seen as well-wishes for those who are ill or injured. Unlike in the original legend, modern senbazuru don't have to be completed by one person alone. They are often collaborative efforts, and whole classes, families, or groups of friends will get together and fold 1,000 cranes to present to a loved one who has been hospitalized.

In addition to these more traditional uses, senbazuru are now created for a wide variety of causes. They've been used to express global support after the 2011 tsunami in Japan, to raise awareness for the conservation efforts of the International Crane Foundation, and to cheer on sports teams. No matter the motivation, folding 1,000 origami cranes will always bring a little more peace, beauty, contemplation, and goodwill into the world. Scroll down to learn how to create your own.

How to make Senbazuru

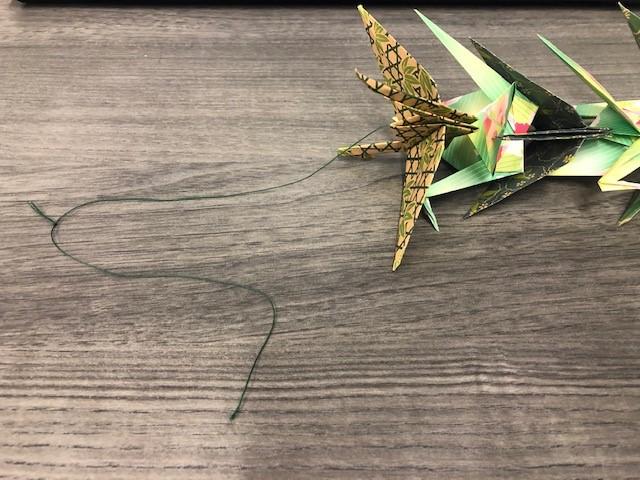

Senbazuru are typically arranged by stringing 25 sets of 40 cranes together. All 25 strings are then tied together at the top, creating a cascading bundle of cranes (pictured left). Today, you can buy kits that include everything you need to make and arrange your 1,000 cranes (origami paper, strings, a needle, and beads). These kits are difficult to find in the United States, but luckily for us the materials are easy to find separately as well.

What you'll need:

1. 1,000 sheets of origami paper (at least. I recommend getting a couple of extra sheets in case of mistakes. If you can't find origami paper, regular paper can be used as well; it just needs to be cut in the shape of a square first.)

2. Around 85 feet of string or fishing twine

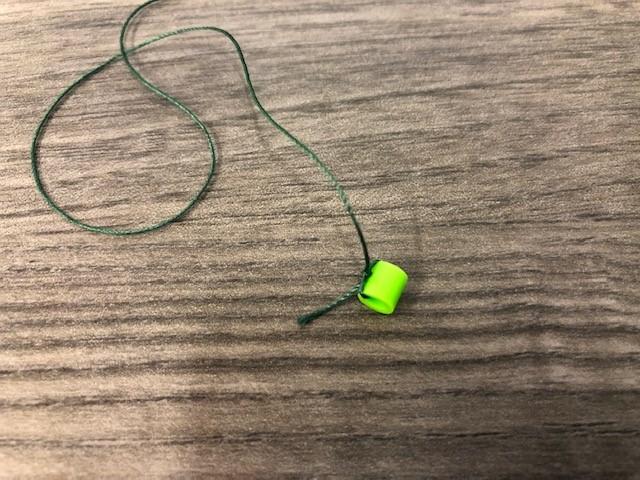

3. Beads (either 25 or 1,000 depending on how you choose to arrange your cranes)

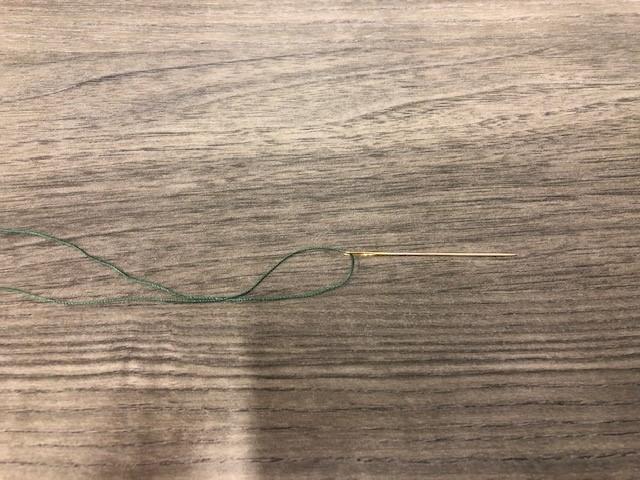

4. A long sewing needle

Part 1: Folding the cranes

The first step in creating senbazuru is to fold A LOT of origami cranes. If you'd like to string the sets of 40 as you go (which is what I recommend), fold 40 before moving on to the next step. If you want to see all of your cranes before deciding how to arrange them, you'll need to fold all 1,000 first.

If you learn best by watching videos, check out one of the origami crane folding tutorials here, here (includes subtitled audio instructions), or here.

If, like me, you learn best from looking at photographs and written instructions, take a look at one of the tutorials here, here, or here.

If you're using rectangle-shaped paper and need to transform it into a square before starting, use the video tutorial here, or the photo tutorial here.

Once you've folded enough origami cranes, move on to part 2.

Part 2: Stringing your cranes

In this tutorial, I'm going to show you how to create traditional strings of 40 cranes, and how to tie them together into a senbazuru. If the standard configuration doesn't appeal to you, though, there are plenty of inventive and fun ways to arrange cranes (a lot of which don't require all 1,000). One popular trend, for example, is to tie shorter strands around an embroidery hoop to create a mobile. Ultimately, however you arrange your cranes will depend on what you'd like to use them for. Doing a quick Google image search for senbazuru can give you a lot of inspiration.

To start, cut around four feet of fishing line or thread and thread your sewing needle. If you're using a thinner thread (such as sewing thread), cut around eight feet and double it.

Next, tie a bead at the bottom of your thread. If you have small beads, all you'll have to do is tie a knot in your thread big enough to keep the bead in place. I only had Perler beads available, so I tied mine with a square knot.

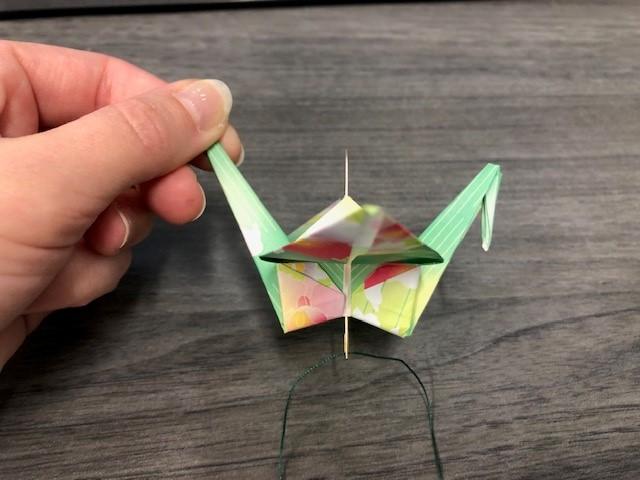

Choose which 40 cranes you'd like to string together. Starting with the crane that will be on the bottom of your string, thread your needle through the small hole in the bottom of your crane and out through the top point of the body.

Pull the crane to the bottom of your thread so it rests on the bead.

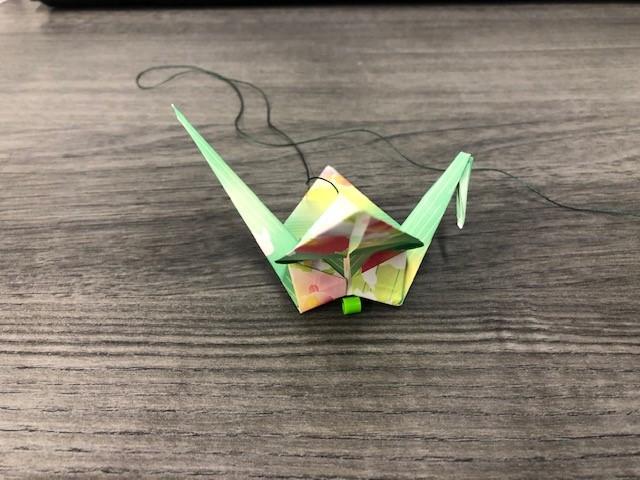

You now have two options when threading the rest of your cranes. You can either go on to repeat the previous two steps with your 39 remaining cranes, or you can 'space' them by stringing a bead in between each crane (both options pictured below). Both methods are common, and the one you pick is entirely up to which one looks best to you. I personally like the way they look without beads, so the rest of the photos in this tutorial won't show the spacing beads.

Once you have all 40 cranes on your string, cut off the excess thread, leaving around 6-8 inches of thread at the top (please ignore the knot in my string. I cut it too short at first and had to extend it. Oops.).

Once you complete your first string, set it aside for now (I suggest temporarily hanging it so the cranes are not in danger of being crushed), and repeat the previous steps to create 24 more strings. Once you have completed all 1,000 cranes (or however many cranes you're interested in folding), it's time to construct the sanbazuru. If you choose to use the traditional 'bundle' configuration (below), simply use the six inches of spare thread at the top of each string to tie them all together. Otherwise, let your creativity run wild and have fun creating your own personalized senbazuru!

Creating a senbazuru is no easy task. It takes a lot of time, effort, and patience (I've been working on mine off and on for years now). Whether you want to make a wish, pray for a loved one's well-being, or simply bring something beautiful into the world, though, the result will always be worth the effort.

To find more origami projects, check out our eSource Creativebug or search for Origami books on Overdrive.

If you would like to learn more about Sadako Sasaki or atomic warfare, please check out the resources below:

The Complete Story of Sadako Sasaki by Sue DiCicco and Masahiro Sasaki

Sadako Sasaki, a young girl of twelve, develops leukemia caused by exposure to the atom bomb dropped on her city of Hiroshima, Japan at the end of WWII. While in the hospital, Sadako learns to fold origami cranes and believes that folding the cranes might lead to the granting of a wish. A loving and compassionate child, Sadako's life inspires her classmates to create a memorial in her honor, to remember all the children impacted by war. Filled with new illustrations and photos of Sadako and her family never before seen by the public, Masahiro Sasaki, Sadako’s older brother, and Sue DiCicco, founder of The Peace Crane Project, tell Sadako’s complete story in English for the first time. Proceeds from this book are shared equally between The Sadako Legacy NPO and The Peace Crane Project .

Sadako and the Thousand Paper Cranes by Eleanor Coerr

Hiroshima Nagasaki: The Real Story of the Atomic Bombings and Their Aftermath by Paul Ham

The first narrative history of the nuclear attack told from both the Japanese and American viewpoints.

Japan 1945. In one of the defining moments of the twentieth century, more than 100,000 people were killed instantly by two atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki by US Air Force B29s. Hundreds of thousands more succumbed to their horrific injuries, or slowly perished of radiation-related sickness.

Hiroshima Nagasaki tells the story of the tragedy through the eyes of the survivors, from the twelve-year-olds forced to work in war factories to the wives and children who faced it alone. Through their harrowing personal testimonies, we are reminded that these were ordinary people, given no warning and no chance to escape the horror.

American leaders claimed that the bombings were 'our least abhorrent choice' and fell strictly on 'military targets'. Even today, most people believe they ended the Pacific War and saved millions of American and Japanese lives. Hiroshima Nagasaki challenges this deep-set perception, revealing that the atomic bombings were the final crippling blow to the Japanese in a stratgic air war waged primarily against civilians.

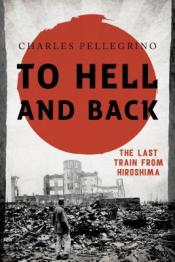

To Hell and Back: The Last Train from Hiroshima by Charles Pellegrino

Drawing on the voices of atomic bomb survivors and the new science of forensic archaeology, Charles Pellegrino describes the events and the aftermath of two days in August when nuclear devices, detonated over Japan, changed life on Earth forever.

To Hell and Back offers readers a stunning, “you are there” time capsule, wrapped in elegant prose. Charles Pellegrino’s scientific authority and close relationship with the A-bomb survivors make his account the most gripping and authoritative ever written.

At the narrative’s core are eyewitness accounts of those who experienced the atomic explosions firsthand—the Japanese civilians on the ground. As the first city targeted, Hiroshima is the focus of most histories. Pellegrino gives equal weight to the bombing of Nagasaki, symbolized by the thirty people who are known to have fled Hiroshima for Nagasaki—where they arrived just in time to survive the second bomb. One of them, Tsutomu Yamaguchi, is the only person who experienced the full effects of both cataclysms within Ground Zero. The second time, the blast effects were diverted around the stairwell behind which Yamaguchi’s office conference was convened—placing him and few others in a shock cocoon that offered protection while the entire building disappeared around them.

Pellegrino weaves spellbinding stories together within an illustrated narrative that challenges the “official report,” showing exactly what happened in Hiroshima and Nagasaki—and why.

Also available from compatible vendors is an enhanced e-book version containing never-before-seen video clips of the survivors, their descendants, and the cities as they are today. Filmed by the author during his research in Japan, these 18 videos are placed throughout the text, taking readers beyond the page and offering an eye-opening and personal way to understand how the effects of the atomic bombs are still felt 70 years after detonation.